on faraway sands, the poets of war spoke to me

i was alone for the day, a whole sumptuous day of solitude and silence. so i, like half the rest of the world it seemed, was pulled to the water’s edge. i carried but a book and a bottle of water. i knew the week ahead would be rough, though i hadn’t a clue yet quite how rough. (two beloved souls, my exact age, died suddenly, one falling to her death*, another simply dying in his sleep.)

the book i carried is one i’d yearned to crack into, and as i sat there allowing its truths to wash over me, as the waves of the lake just across the sand washed over the shoreline again and again, i felt every drop of its anguish and truth. it was a book of poems written by thirty poets in gaza, and four from the west bank.

once upon a time, for ten good years, i gathered up each month for the chicago tribune a collection of three books that had most stirred my soul. they might be children’s books, or poetries, or memoirs and stories of the holiest people. the gatherings were vast, and some of those publishers still send me books, knowing full well my readers now are not the millions from the tribune and beyond, but rather the cherished friends of the chair.

this book i bring today is one worth clutching in your hands, pressing hard against your heart. it might be even more poignant against the improbable news that a cease fire in gaza has begun and some twenty living israeli hostages will soon be released.

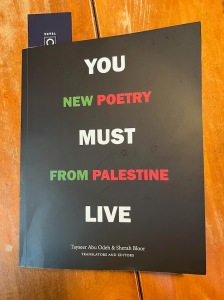

its title, you must live: new poetry from palestine (copper canyon press, 2025), only begins to tell the story, only hints at the horrors and tendernesses within. but you can hear the pleas, the cries rising up from the rubble. it’s a bilingual anthology of poetries from gaza and the west bank, translated from the arabic and edited by Tayseer Abu Odeh and Sherah Bloor, with guest editor Jorie Graham, and it’s written not by poets who’ve somehow escaped, left behind the ravages of war, but rather it’s written by those still there. in poring over its pages—slowly and with prayerful intent—you hear the murmurs perhaps unheard by anyone else, you hear the lone voice rising from dust, you hear the whimper of a child left alone in the world, in the shattered brokenness of a world that no longer stands.

“especially now,” the editors write, “it is crucial to attend to those whose voices are under threat of elimination.”

ocean vuong called it “a light beam of a collection in our dark hours.” ilya kaminsky, the great poet most famous for his deaf republic, has written that it’s a book “filled with poems of utter urgency, poems that give us wisdom, in the face of devastation, in spite of devastation.”

i was as moved by the story behind the poems, as by some of the poems themselves. for starters, editing in a war zone is no feat for the timid. the editors write that at first they didn’t realize that every time someone’s phone connected to a satellite (to reply to an editing question) they became a target. to get a clear signal, the editors write, meant a life-or-death decision: standing atop rubble is where the signal is sharpest, and yet of course that means the poet is risking her or his life to reply.

consider that.

the editors write too that every time a reply did come through, be it a response about punctuation or diction, the editors sighed with relief. “they were still with us.” imagine being willing to die over a comma rather than a semicolon. consider that the next time you make a simple correction in a sentence you’re typing.

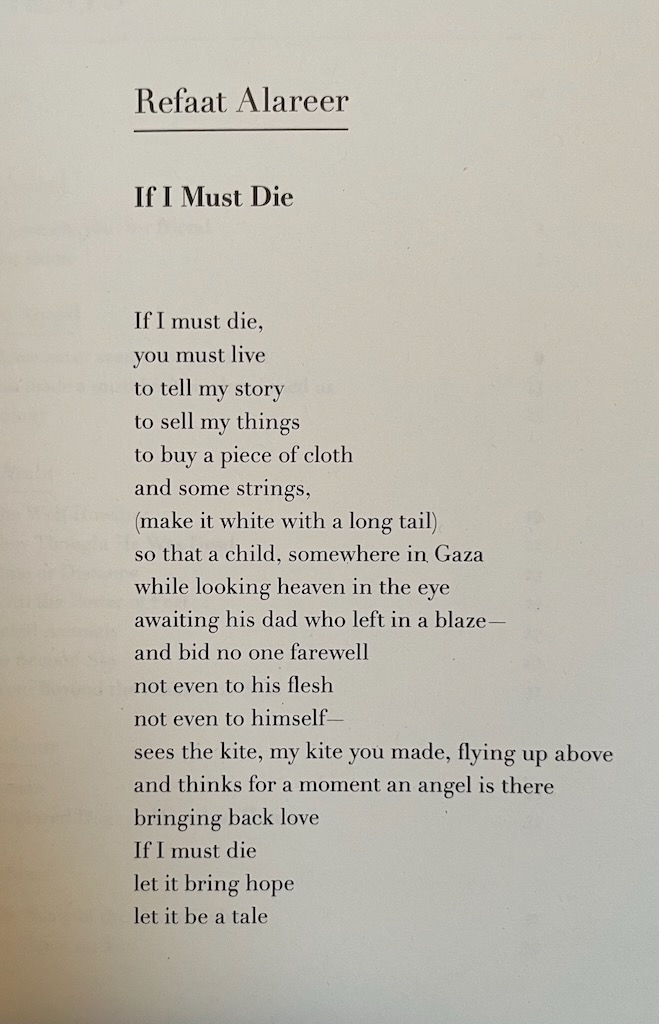

the collection begins with a poem that’s become fairly widely known, “if i must die,” by the late Refaat Alareer. the editors write: “this poem stands in for all those poets we failed to reach in time. their poems—chalked onto collapsed walls, or on the blackboards of schools-turned-shelters-turned-bombsites, traced in sand, or shared in private messages—will never reach us.”

the silence is stunning. the silence demands our reverence.

the editors call the poems a “poetry of witness,” speaking from a war zone deadly for journalists, a war zone where so many stories would otherwise go untold. the poets paint the portrait. and it is seizing with humanity. humanity crushed. humanity pummeled. human refusing to extinguish its tender, fragile beauties. we must know what we, humanity all, have wrought.

here are a few samples, barely enough to give you a sense of the pathos within, the pathos that rises from this old globe like a poisonous cloud desperate for one breath of air….

here is the poet Waleed al-Aqqad’s elegy for a young friend, set at the boy’s funeral, and tenderly describing the mutilations of his war-torn body:

We said goodbye

to you in your small death like the death

of sparrows.

We rearranged you.

We placed your severed hand across your chest,

covered your wounds with flowers,

cried as you wanted.

or this, from Ala’a al-Qatrawi’s poem to her children, two daughters and two sons, all under the age of six, all killed in an air strike on their home. she addresses her babies in heaven, offers her own body parts to her daughter, Orchida, as if she could piece her body back into her embrace:

And give my lungs to her.

Without them, maybe she suffocated.

Maybe she couldn’t call my name.

The rubble would have been too heavy for her.

it is wrenching to read. all of it. page after page, i read slowly, as if a dirge. i sat on a bench on the sand thousands and thousands of miles away. that seemed cruel, unfair, that i should be hearing the sounds of a day at a beach, when the sounds of war pressed on. and the words of new poets would again go unheard.

to those who understand the power of words, to those who dared to gather poems out from the rubble, bless you, and bless you, and may peace, everlasting peace, at last come to the holy land.

this hard week ends with a few sparks of hope: first, word of the cease fire and the imminent promised release of 20 living israeli hostages, and the bodies of 26 confirmed dead. and, in the immediate wake of that, the nobel peace prize was awarded this morning to venezuela’s “iron lady,” maria corina machado. the committees’ citation reads: “She is receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for her tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela and for her struggle to achieve a just and peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy.”

where did you find hope in these hard times?

*joannie barth was a most beloved reader of the chair. she lived in evergreen, colorado. was the right-hand everything to the best-selling author philip yancey. she and i had gone to college together, but mostly got to know each other’s souls through this ol’ chair. she would send notes radiant with love, with a faith that couldn’t be shaken. she shared her own heart’s ache, an ache i now hold for her. i was with her less than a year ago, and as she always had, she lit up a room. her smile rose from a deep deep place. a week ago, she was rock climbing. and the belts gave out. she died instantly. not at all surprisingly, i feel her closer than ever. she was, and is, an angel.