quiet christmas, red-ringed edition

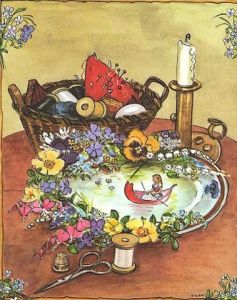

more than anything, i yearn for the quiet of christmas, the early morning silence when it’s just me puttering about the kitchen, cranking the oven, simmering spices on the stove. i take my morning prayer by flickering candle flame. or beneath the morning stars. or beside the woodsy fir, now strung with lights and berries, standing proud beside the ticking clock that chimes the hours.

i love listening for the first of the footsteps thumping onto the floorboards overhead, and the creaking of the old oak that follows. but long before that longed-for stirring breaks the silence, it’s into the depths of quiet that i surrender, that i’ve been waiting for all these weeks. the old house before its stirring. when it’s just barely breathing. and christmas is finally at the door.

it’s in that silence that i most absorbingly slip into the dusky hours of that ancient, ancient night, when amid the vastly-vaulted holy land, beneath the rough-hewn rafters of a barn, down low where the straw was matted, where the creatures intoned their moans and mews and cooing, a newborn babe let out a human cry. i like to imagine i’m peeking out from behind a post. i sometimes imagine the laboring mother reaching out her hand, reaching out for strength in the form of someone else’s flesh and delicate bone, reaching for another hand—my hand—to hold onto hers, to wipe her brow, her tears, to kneel down beside her and whisper certainties. “you got this,” i imagine saying, as these three words have so often scaffolded me in my own hours of trembling fears.

but this christmas is not going to be like any other christmas. it’s not even like last year’s most unfamiliar christmas, when we all but hunkered down, when we awaited the vaccine just peeking over the horizon, when hope felt not too far off.

no, this christmas, we’re all upside down again. it’s all changed and changing fast. as fast as that red-ringed variant omicron is mutating, is doubling in numbers inside some of us, our hopes and plans for christmas are changing too.

there is abundant heartbreak this christmas. and here, on the very eve of christmas day, i don’t yet know what tomorrow will bring. but i’m willing to bed i won’t be leaving my bed.

given the headlines––the wildfire that is omicron––there’s a mighty fair chance your christmas is as tumbled up as ours.

we’ve an uninvited visitor here, one who snuck in through the back door and turned everything inside out and slanted. yes, covid came, and in very short order canceled someone’s surgery, and canceled someone else’s flight from california. covid came and sent one of us all but seeing stars, she was so gulpingly alarmed. after all, i’ve lived the last nearly two years doing everything i could to lope at least two steps ahead: for months i was among the ones who washed every single grocery bag or box or pint hauled into this old house; i steered clear of crowds, wore not one but two masks unless alone in the woods, or tracing the lakeshore’s edge. met ones i love harbored on the front stoop a good twelve feet away. washed my hands to happy birthday thrice. (if twice was recommended, i opted always for the extra round of public health insurance.)

but covid caught up to us. my firstborn—home for the first christmas in two years—is quarantined in the room at the top of the stairs. i was quarantined in my little writing room until my PCR came back negative early yesterday morn. for two long days, i was calling the book-stacked chamber my covid cottage, my covid christmas cottage.

and now, after a long night with thermometer under tongue, i’m all but sure the red-ringed virus dodged the swab but has me in its clutches, since i feel more awful by the hour. i’m thinking omicron is wily, and mighty good at playing hide-and-seek. i’ll test again this morning. (bless the neighbors who drove home from ohio, where supply is far more abundant, with a wee stash of impossible-to-find DIY covid tests.)

most of all, i’ve worried about my mama, who does not want to be alone on christmas day, but whom we don’t want felled by this nasty, nasty scourge. dear God, don’t let her get it.

all the last minute upside-down-ness has clearly pointed to one simple single certain truth: if we can be gathered with the ones we love, under the same roof, by zoom or phone or mental telepathy, well then we’re blessed as blessed could be.

this is not the way i imagined it, whispering christmas wishes through a crack beneath the door, leaving packages on the tray that ferries food and dishes in and out of the sickroom. too contagious to wander down the stairs and daydream by the light-strung tree. but here’s what matters: we are emphatically and undeniably all under one single roof.

which, after all, is the answer to a hundred prayers. it’s what we lacked last year. and some iteration of what i wished for this year.

while we untangle uncertainties here on the homefront, i still stand ready to unfurl a christmas morning’s benediction.

a prayer for quiet christmas

dear God of starlit dawn, dear God of Light now coming, as we gather up this year, gather up the sorrows and the sweetness, hear our deepest cries. let us love even when our hearts get bumped and bruised. let us be gentle in the harshest hours. let us keep upright even when we’re wobbling. let us hold onto hope. let us seize the blessings as they unfold within our reach. lift up our tender memories, the ones we’ve loved and lost this year. let us carry forward their inextinguishable flame, and keep their incandescence blazing. dear God, as we bow down and bend our knees, let us behold the newborn wonder, and do all we can to absorb the holy light of this most silent silent night.

merry blessed christmas to each and every someone who wanders by the chair. may you be well, and hold tight to all your blessings.