iterations of love

the God of every religion tells us to do it. commands us: love thy neighbor as thyself.

i’ve felt it in my own life, know it to be a force that transcends time, space, and matter. i’ve felt it all but align planets whose orbits were out of whack. i’ve felt it pierce through to the core of me, prompt me to reach down and seize a source, a muscle, i didn’t know that i had. it’s made me more than i ever imagined i could be. lured me out of mighty dark years.

love, thank heaven, is patient. love is keenly perceptive. love, often, won’t take No for an answer.

i’ve felt it shrink distance, make the sound coming through the telephone as close as if we were sidled, thigh to thigh touching, on the seat of a couch in the very same room.

i’ve heard it in barely audible whispers, and in shouts across the corridors of an airport, a hospital, a college campus––a sound so ebullient my heart leaps to quicken its pace.

i’ve spent my life learning how to do it. keeping close watch on the ones i encounter who do it the best. the most emphatically.

i’ve learned it from the little bent man who perched on a hydrant, befriending the pigeons. flocks and flocks of pigeons, he lovingly tended. even in the face of taunts and jeers from the cars passing by.

i’ve learned it from my first best friend who knew without asking how deeply it hurt, how tender it felt to be seen in shadow and light.

i’ve learned it from my long-ago landlady, the one who would knock at my door, come dinnertime, and hand me a hot steaming bowl of avgolemeno, the egg-and-lemon-rich chicken-rice soup that serves as Greek penicillin, and cured what ailed me no matter how awful the day.

i’ve learned it from a 12-year-old girl who lay in a hospital bed, her legs unable to move, paralyzed from the waist down by a tumor lodged in her spine. i’ll never forget the glimmer in her eye, as she looked up and laughed, as she handed me her hand-made papier-mâché green pumpkin head, the one she’d made flat on her back, and with which she crowned me her Irish Pumpkin Queen of a hospital nurse.

i’ve learned it, and felt it: in the canyon of grief, in the vice hold of fear, and in long seasons of haunting despair. it’s the ineffable force with the power to pull us up off the ground, inch us just a little bit forward, and shake off the worries that freeze us in our tracks.

my hunch is that someone at hallmark international invented today, the day in which pink paper hearts are soared hither and yon. or maybe it was the three catholic saints, all named valentine or valentinus, and, as was so often the story, all of whom were martyred for breaking some reason or rule. in the case of third century rome, a priest named valentine defied the emporer who’d ruled that single men made better soldiers than those with a wife, and thus outlawed marriage. valiant valentine, seeing the injustice in the loveless decree, kept about the business of marrying young sweethearts in secret. for this, he lost his head.

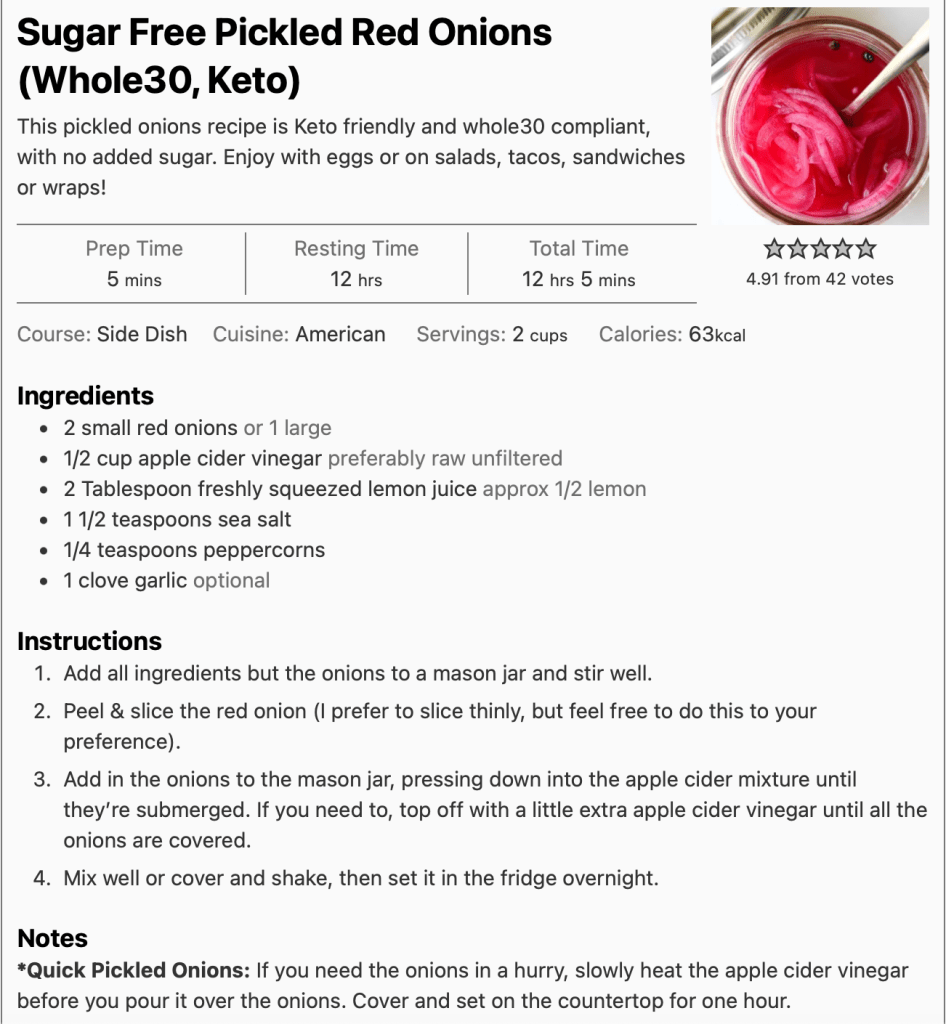

earlier still, pagans seized the midpoint, or ides, of the month––february 15––as Lupercalia, a fertility festival dedicated to Faunus, the roman god of agriculture, and to Romulus and Remus, the founders of rome. a priestly order of roman pagans, the Luperci, gathered at the secret cave where Rom and Rem were thought to have been raised by she-wolves, to sacrifice a goat, which they then stripped of its hide, and sliced into strips. then, according to historians, “they would dip [the strips] into the sacrificial blood and take to the streets, gently slapping both women and crop fields with the goat hide.”*

maybe pink paper hearts are, after all, a step in the right romantic direction.

*postscript on those slap-happy romans: far from being fearful of the bloody slaps, young roman women were said to welcome the mark of the bloody hides, for it was thought to make them more fertile in the year to come.

lifting the day out of its purely-romantic framing, here are three takes on iterations of love, reminding us of the evolution of love across the decades of marriage, and the love of this one sacred Earth we’ve been given to tend:

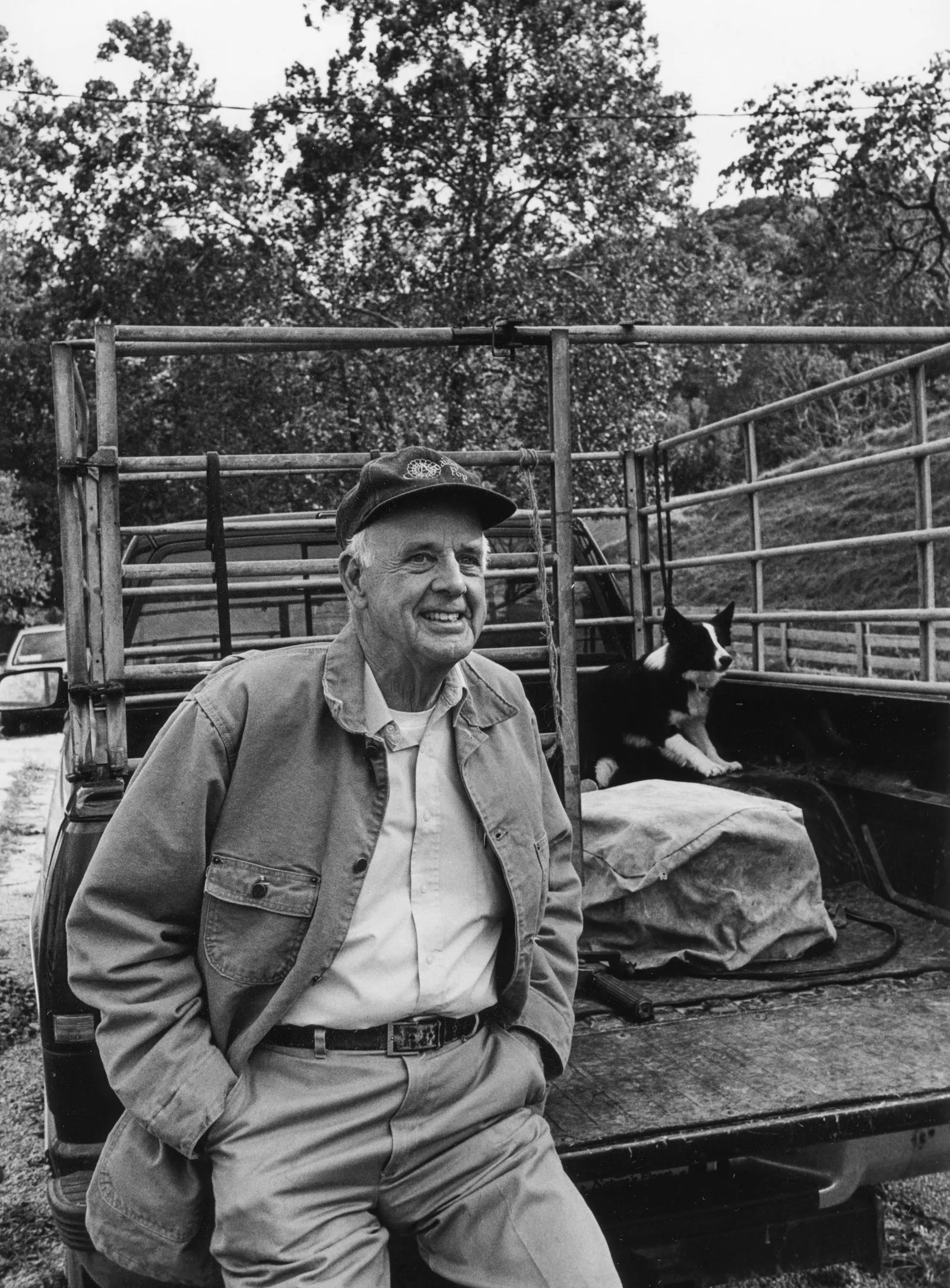

first up, the sage from kentucky, farmer-poet-secular priest wendell berry, from a much longer poem, but i was drawn to these three parts, meditations on a long and deepening love…

excerpts from The Country of Marriage

by Wendell Berry

III.

Sometimes our life reminds me

of a forest in which there is a graceful clearing

and in that opening a house,

an orchard and garden,

comfortable shades, and flowers

red and yellow in the sun, a pattern

made in the light for the light to return to.

The forest is mostly dark, its ways

to be made anew day after day, the dark

richer than the light and more blessed,

provided we stay brave

enough to keep on going in.

IV.

How many times have I come to you out of my head

with joy, if ever a man was,

for to approach you I have given up the light

and all directions. I come to you

lost, wholly trusting as a man who goes

into the forest unarmed. It is as though I descend

slowly earthward out of the air. I rest in peace

in you, when I arrive at last.

V.

Our bond is no little economy based on the exchange

of my love and work for yours, so much for so much

of an expendable fund. We don’t know what its limits are–

that puts us in the dark. We are more together

than we know, how else could we keep on discovering

we are more together than we thought?

You are the known way leading always to the unknown,

and you are the known place to which the unknown is always

leading me back. More blessed in you than I know,

I possess nothing worthy to give you, nothing

not belittled by my saying that I possess it.

Even an hour of love is a moral predicament, a blessing

a man may be hard up to be worthy of. He can only

accept it, as a plant accepts from all the bounty of the light

enough to live, and then accepts the dark,

passing unencumbered back to the earth, as I

have fallen tine and again from the great strength

of my desire, helpless, into your arms.

and the belle of amherst turns our attention to this world that keeps loving us, despite the ways we batter it, and ignore it…

This world is just a little place, just the red in the sky,

before the sun rises, so let us keep fast hold of hands,

that when the birds begin, none of us be missing.

— Emily Dickinson, in a letter, 1860

and finally, the late great naturalist and essayist Barry Lopez, on how to be awake to this still blessed world, from the foreword to Earthly Love, a 2020 anthology from Orion magazine. He is describing walking a vast landscape––a spinifex plain, or grassy coastal dunes, in North-Central Australia––for the first time, but the wisdom is how to attend to a deepening love:

My goal that day was intimacy — the tactile, olfactory, visual, and sonic details of what, to most people in my culture, would appear to be a wasteland. This simple technique of awareness had long been my way to open a conversation with any unfamiliar landscape. Who are you? I would ask. How do I say your name? May I sit down? Should I go now? Over the years I’d found this way of approaching whatever was new to me consistently useful: establish mutual trust, become vulnerable to the place, then hope for some reciprocity and perhaps even intimacy. You might choose to handle an encounter with a stranger you wanted to get to know better in the same way. Each person, I think, finds their own way into an unknown world like this spinifex plain; we’re all by definition naive about the new, but unless you intend to end up alone in your life, it seems to me you must find some way in a new place — or with a new person — to break free of the notion that you can be certain of what or whom you’ve actually encountered. You must, at the very least, establish a truce with realities not your own, whether you’re speaking about the innate truth and aura of a landscape or a person.

. . . I wanted to open myself up as fully as I could to the possibility of loving this place, in some way; but to approach that goal, I had first to come to know it. As is sometimes the case with other types of aquaintanceships, to suddenly love without really knowing is to opt for romance, not commitment and obligation.

and, later in the same essay, his call to attention for a world suffering from what he quite plainly calls, “a failure to love,” a message of urgency on a day in which love, in its many many iterations, is held up to the light.

EVIDENCE OF THE failure to love is everywhere around us. To contemplate what it is to love today brings us up against reefs of darkness and walls of despair. If we are to manage the havoc — ocean acidification, corporate malfeasance and government corruption, endless war — we have to reimagine what it means to live lives that matter, or we will only continue to push on with the unwarranted hope that things will work out. We need to step into a deeper conversation about enchantment and agape, and to actively explore a greater capacity to love other humans. The old ideas — the crushing immorality of maintaining the nation-state, the life-destroying beliefs that to care for others is to be weak and that to be generous is to be foolish — can have no future with us.

It is more important now to be in love than to be in power.

who were some of your great teachers of love?