keening.

the winds have been howling all night, a rushing, a roaring of air on amphetamines. sometimes the sound rises in pitch, almost a keening, the sound of a soul in mourning.

keening, a word that draws me half around the world to the banshees of that faraway island from which my people came (a good half of my people, actually, but it seems the half i’m rooted in). it’s a word that places me in a dark and damp room where a fire roars, and the people are circled in sorrow, cloaked in black woolen wraps. swaying and rocking, the sound that rises up is the sound that lives at the pit of us, the sound that rises when our heart or our soul is shattered. cracked wide open. it’s the ooze of anguish that comes without volition. keening sometimes comes without knowing. it just is. it’s primal. a reservoir so deep inside us it takes velocities of sorrow to tap into it, to draw from its well.

i might have keened once or twice, but i barely remember. both times someone had died, and it felt like part of me did as well. i remember the sound, remember i barely knew where it rose from, or that i’d had it inside.

the God who imagined us imagined so far beyond the imaginable. the God who imagined us gave us a sound, buried it deep, deep inside, where it awaits necessity. there are in our lives times when only that keening will do. that high pitched guttural whoosh that captures the unspeakable, a whoosh that rises and falls, traces the scale from basso, the animal roar, to mezzo soprano, up high where it’s piercing.

and why would the wind be keening?

look around.

listen.

don’t let us dull to the litany.

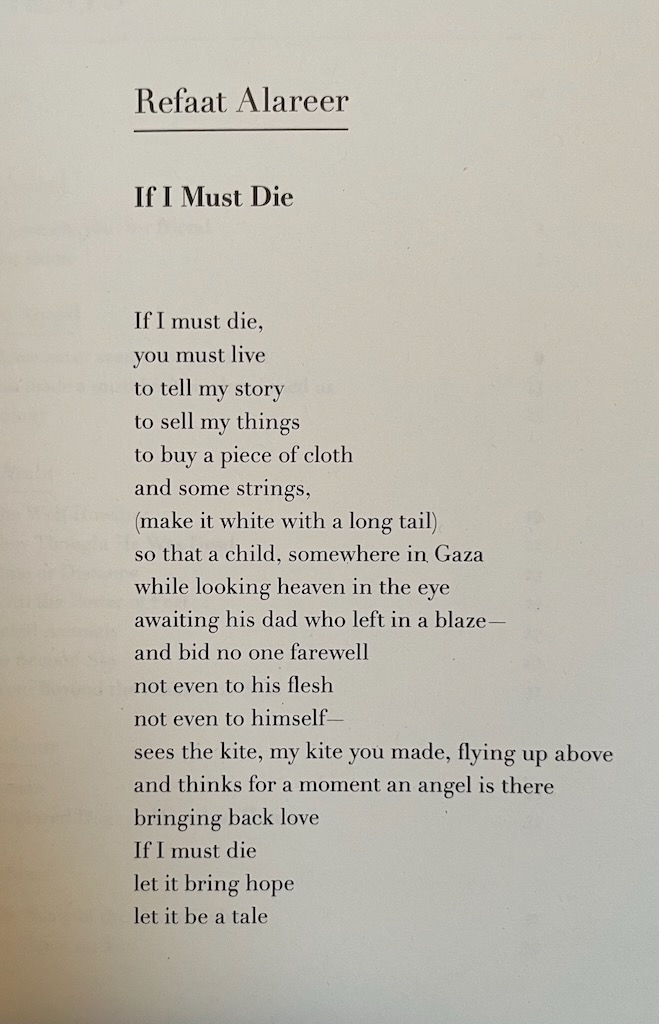

waking up to find we live in a pariah nation is one. but that’s almost too big for my head. i tend to operate in the finer grain. and the closest i came to keening this week was the news that the poet had been shot through the head.

what poet, you might ask?

the one in minnesota. the one whose first description i read was “37-year-old, mother of a six-year-old, award-winning poet.”

who shoots a poet? how often does the descriptor of a violent death include the word poet?

poets are porous. poets live in the world permeable to the little-noticed. poets process what’s breathtaking and put it, miraculously, to words. poets, the ones i love, the ones whose words put form and frame to unutterable parts of me, they’re among the most gentle-souled humans i’ve known.

renée good was a poet. a mother. and she died at 37, in the front seat of her maroon van we’ve all now watched over and over.

renée good, back when she went by the name renée nicole macklin, won the 2020 academy of american poets prize. that’s not a prize for a piker. that’s a real-deal prize, a trophy worth tucking on the highest shelf in your house. she won it for a poem curiously titled “On Learning to Dissect Fetal Pigs.” now, that might not be the first thing that stirs me to want to write a poem. but poets begin in curious places sometimes and take us into terrain where wisdom or epiphany comes.

when we become a nation where a poet is shot through the windshield, just minutes after dropping her six-year-old off at school, we need to ask who in the world we’ve become. it only becomes more twisted when we can see for ourselves how the scene unfolded, and the people in charge, the ones holding the guns, the ones not letting a doctor rush to the scene, tell us that we didn’t see what we saw.

i wonder how apt this headline would be: good is dead.

that would be the headline atop the poet’s obituary. rachel good, award-winning poet and mother of three, was shot through the head. by federal agents. who then refused to let a doctor rush to the front seat of her bloodied, bloodied minivan. and waited too many fading heartbeats before giving the okay to call 9-1-1.

no wonder the wind is keening.

no wonder the world is tapping into its most guttural cries.

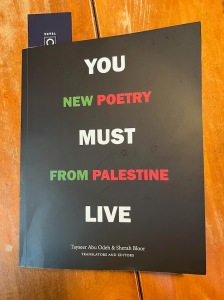

not long before i’d found myself tripping over the violent death of rachel good, i’d been thinking deeply about poets. thinking about a breed of poets i’d likened to “a tribe of saintesses.” that’s a feminization of saint, an intentional genderizing, if you will, because the poets i’m most drawn to might technically, and in an old-time world, be coined poetesses, and because the ones to which i am most deeply drawn are ones who weave the sacred, even the liturgical, into the vernacular from which they write. because the saintesses to whom i am most drawn are the ones whose verse scans the divine, shimmers at the edge of the ineffable, catches me unaware, but grounds me in a certainty more certain than many a gospel, i turn to them for edification and plain old uplift of my weary soul.

i keep them in close reach.

sitting just beside me here at this old maple table are two such poet saints, the ones whose lines leave me gasping, my spine tingling as if something holy has just wafted by and through me. because it has.

here’s one. her name is kathleen hirsch, and this is from her mending prayer rugs (finishing line press, 2025). it’s the last stanza of her poem “prayer rugs” (emphasis mine):

I bend in blessing toward all that breathes

May each hour enlarge the pattern—

rose dawn, wind song, tender shoots of faith—

that I may see the weft of the hidden weaver.

or, also sitting right by my elbow, jan richardson’s how the stars get in your bones: a book of blessings (wanton gospeller press, 2025), i flip through pages and pluck just one, titled “the midwife’s prayer.” it begins:

Keep screaming, little baby girl.

Keep practicing using those lungs

and do not stop,

because hollering will help

to ease the shock

every time you go through

another birth.

the saintesses, i swear, speak from a godly vernacular. they see deeper than the rest of us, dwell deeper too. their gift is the gift taken away at Babel. while all the rest of us were stripped of the powers of universal understanding, the saintesses kept on. they speak words that speak to all of us—if we listen closely. if we trace our fingers across the lines they offer, sacramental lines, lines that lift off the page, lift us off the page and into the transcendent, where for just a moment we get to reside.

i don’t know the rest of rachel good’s poems. but i know she was a poet. and the silence where once she spun the words of the unspoken, the little-heard voice, that silence now is cacophonous.

and even the winds are keening.

you can read the whole of rachel good’s prize-winning fetal-pig poem here.

and here are the first few lines…

On Learning to Dissect Fetal Pigs

by Renée Nicole Macklin

i want back my rocking chairs,

solipsist sunsets,

& coastal jungle sounds that are tercets from cicadas and pentameter from the hairy legs of cockroaches.

i’ve donated bibles to thrift stores

(mashed them in plastic trash bags with an acidic himalayan salt lamp—

the post-baptism bibles, the ones plucked from street corners from the meaty hands of zealots, the dumbed-down, easy-to-read, parasitic kind):

what shall we do to quell the need for keening? and what poets draw you into the depths of the Holy?