we are all filled with tears. if only we notice.

i am, as i so often am, late to the game. late to the nick cave game. i’ve known of his profound capacity to pierce the armament of the contemporary human wardrobe: the shield that keeps us at a distance from our own vulnerability. i’d heard rumor that he was a writer’s writer. but i’d never really dived in.

until now.

when a beloved, beloved friend sent me a letter he’d written that rang so, so close to truth — to my truth, anyway — i signed right up for more, more, more.

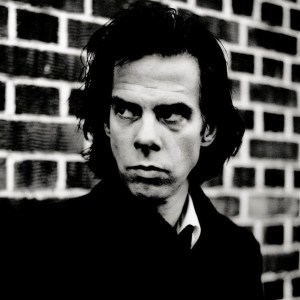

nick cave, in case he’s floated outside your circle of knowing, is, in a nutshell, a once-upon-a-time choir boy from australia, who went on to a wild ride through the early punk rock scene, and with his shock of black black hair and an emaciated profile, might aptly be described as a goth pioneer (note to mom: that means someone who takes on a wardrobe that’s something of a cross between a corpse and your most ghoulish uncle, and wallows in the literature and the language and the aesthetic of similar darkness, verging on the macabre). in time, he moved into the quieter, more contemplative lane of soulful song. his trademark, a baritone so deep it feels pulled from igneous rock, is fittingly in sync with the haunting, soulful lyrics he’s come to write.

i’d known that tragedy struck dear nick, when his then 15-year-old son, arthur, fell from a cliff near brighton, england, and seven years later another son, jethro, died at 31, a death he doesn’t talk about, abiding by the wishes of jethro’s mother. i’d read bits of his writings about grief.

It seems to me, that if we love, we grieve. That’s the deal. That’s the pact. Grief and love are forever intertwined. Grief is the terrible reminder of the depths of our love and, like love, grief is non-negotiable. There is a vastness to grief that overwhelms our minuscule selves. We are tiny, trembling clusters of atoms subsumed within grief’s awesome presence. It occupies the core of our being and extends through our fingers to the limits of the universe. Within that whirling gyre all manner of madnesses exist; ghosts and spirits and dream visitations, and everything else that we, in our anguish, will into existence. These are precious gifts that are as valid and as real as we need them to be. They are the spirit guides that lead us out of the darkness.

but never have i read any of the longer works i will now go find (faith, hope and carnage, an extended interview with the journalist seán o’hagan.) what’s intrigued me most, in poking around and gathering bits in the ways of magpie (a bird known for scavenging trinkets hither and yon), is his take on religion. it’s always the soulful entrée where i find my curiosities leading me. this paragraph alone shouts, read, read, read more to me….

Cave is an avid reader of the Bible. In his recorded lectures on music and songwriting, Cave said that any true love song is a song for God, and ascribed the mellowing of his music to a shift in focus from the Old Testament to the New. He has spoken too of what attracts him to belief in God: “One of the things that excites me about belief in God is the notion that it is unbelievable, irrational and sometimes absurd.”When asked if he had interest in religions outside of Christianity, Cave quipped that he had a passing, sceptical interest but was a “hammer-and-nails kind of guy.” Despite this, Cave has also said he is critical of organised religion. When interviewed by Jarvis Cocker of Pulp on 12 September 2010, for his BBC Radio 6 show Jarvis Cocker’s Sunday Service, Cave said that “I believe in God in spite of religion, not because of it.”

*(emphasis, mine; in the case of “hammer-and-nails” it just struck my funny bone.)

the red hand files is the name of his blog, where he writes perhaps his most spontaneous writing (the hidden beauty of blogging [among the uglier words in the lexicon]). started years ago, it was a place for nick cave fans to send him questions, questions he’d sift through and choose to answer—or not. it seems to have morphed into a place of profound nakedness, another name for truth in unprotected, unshielded, undressed form.

here, the letter that drew me in, or most of that letter anyway:

As the ground shifts and slides beneath us, and the world hardens around its particular views, I become increasingly uncertain and less self-assured. I am neither on the left nor on the right, finding both sides, as they mainly present themselves, indefensible and unrecognisable. I am essentially a liberal-leaning, spiritual conservative with a small ‘c’, which, to me, isn’t a political stance, rather it is a matter of temperament. I have a devotional nature, and I see the world as broken but beautiful, believing that it is our urgent and moral duty to repair it where we can and not to cause further harm, or worse, wilfully usher in its destruction. I think we consist of more than mere atoms crashing into each other, and that we are, instead, beings of vast potential, placed on this earth for a reason – to magnify, as best we can, that which is beautiful and true. I believe we have an obligation to assist those who are genuinely marginalised, oppressed, or sorrowful in a way that is helpful and constructive and not to exploit their suffering for our own professional advancement or personal survival. I have an acute and well-earned understanding of the nature of loss and know in my bones how easy it is for something to break, and how difficult it is to put it back together. Therefore, I am cautious with the world and try to treat all its inhabitants with care.

I am comfortable with doubt and am constitutionally resistant to moral certainty, herd mentality and dogma. I am disturbed on a fundamental level by the self-serving, toddler politics of some of my counterparts – I do not believe that silence is violence, complicity, or a lack of courage, but rather that silence is often the preferred option when one does not know what they are talking about, or is doubtful, or conflicted – which, for me, is most of the time. I am mainly at ease with not knowing and find this a spiritually and creatively dynamic position. I believe that there are times when it is almost a sacred duty to shut the fuck up.

I’m not particularly concerned about where people stand – I’ve met some of the finest individuals from across the political spectrum. In fact, I take pride and immense pleasure in having friends with divergent views. My life is significantly more interesting and colourful with them in it.

Perhaps this all amounts to very little, but I suppose, in the end, I value deeds over words. I see my own role as a musician, songwriter, and letter writer as actively serving the soul of the world, and I’ve come to understand that this is the position that I must adopt in order to attempt to cultivate genuine change. In fact, I am now beginning to understand where I do stand, Alistair – I stand with the world, in its goodness and beauty. In these hysterical, monochromatic, embattled times, I call to its soul, the way musicians can, to its grieving and broken nature, to its misplaced meaning, to its fragile and flickering spirit. I sing to it, praise it, encourage it, and strive to improve it – in adoration, reconciliation, and leaping faith.

Love, Nick

but that’s not all….

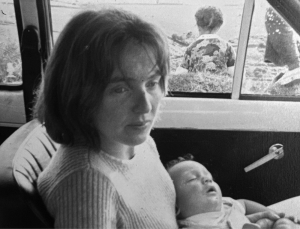

maybe what we need in this age is to move beyond words. to use our eyes more than our ears. to look and look closely at the common bonds of our humanity, and herein is precisely the study we might need, to see the human visage wrought by sorrow, or grief: on the brink of tears, fighting tears, to watch the flinching of muscle, the biting of lips, the contortion of muscle, pulled by nerves tied to whatever is the emotional core of us. to see how the human face on the brink of tears is sooooo deeply universally understood, felt, responded to. maybe in that place of wordlessness we can remember that we are all one, of one species, and that within us all is the emotion called grief, called sorrow. and we’d do well to remember that we are all always on the verge of brokenness. and, too, we might be the arms that reach out to dry the tear, to hold the quivering shoulders, to brace the wobbling spine against whatever strength we might muster. maybe we need to remember how tender we all are, somewhere, somewhere deep inside…..

only one poem this week, and it wasn’t actually written as a poem, but laid out that way here it works mightily. it’s excerpted from abolitionist Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” address, in the version published in 1863. The speech was originally delivered in the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. we might do well to ask, in the face of so much inhumanity, if swapping out the word “human” for “woman” stirs its own seeds of compassion….i am bereft; hollowed, haunted by the stories of immigrants pulled from their churches, their cars, their homes, flung to the ground, stomped on, kicked, living in fear…..

but this, as written, is more than mighty as is…..

Ain’t I A Woman?

That man over there

says that women

need to be helped into carriages,

and lifted over ditches,

and to have the best place everywhere.

Nobody ever helps me into carriages,

or over mud-puddles,

or gives me any best place!

And ain’t I a woman?

Look at me! Look at my arm!

I have ploughed and planted,

and gathered into barns,

and no man could head me!

And ain’t I a woman?

I could work as much

and eat as much as a man —

when I could get it —

and bear the lash as well!

And ain’t I a woman?

I have borne thirteen children,

and seen most all sold off to slavery,

and when I cried out

with my mother’s grief,

none but Jesus heard me!

And ain’t I a woman?

. . .

Then that little man in black there,

he says women can’t have

as much rights as men,

’cause Christ wasn’t a woman!

Where did your Christ come from?

Where did your Christ come from?

From God and a woman!

Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made

was strong enough to turn

the world upside down all alone,

these women together

ought to be able to turn it back,

and get it right side up again!

And now they is asking to do it,

the men better let them!

+ Sojourner Truth

because you are all so wise in so many ways, what thoughts might you add to a conversation on love and grief, and the intermingling therein?

i’m off to my 50th high school reunion this weekend, a date that gives me pause, as it was one of the tenderest times in my life 50 years ago, a time that marked me through all these years. it was a steep uphill climb for a long time there. and thank holy God i lived long enough to get here. my prayer is that those who show up find compassion and grace, and that those who choose to stay home look around and see lives that have grown beyond the bounds of whatever have been the obstacles.

and i pray, oh i pray, for this world. no kings rally tomorrow….i heard a story this week about the not-far-away catholic church where ICE agents filled the parking lot during spanish-language mass, targeting the prayerful inside. so the priest becalmed those in the pews, locked the church doors, promised protection to his flock, and a brigade of rapid-response volunteers drove parishioners safely to their homes. cars had to be left behind. prayers were laced with terror. this is not the america my uncle died for, bayoneted in the night in a tent on iwo jima….

as my beloved friend fanny put it, “they come after us because we’re brown.”

**thank you, laura, for sending me nick….