tefillah (תפילה) for a sweet new year in the season of awe

it is the soft dawn of a new year here, the jewish new year, an ancient calendar i’ve been drawn into, enfolded by, graced by, for all the decades since i met my beloved. he was the one who caught my eye back in the long ago, leaving the newsroom before sundown on friday nights to go to synagogue. i was moved by that devotion. leaving the newsroom on a friday night, back in the days when the big fat sunday newspaper was being “put to bed,” all the sections laid out, the stories edited, photos cropped and captioned, leaving the newsroom before deadline on a friday night meant you were breaking a mold. and you’d better have had a very good reason.

he broke my mold, all right, that tall bespectacled fellow loping toward the door. broke open a love of sacred creation, broke open an ancient text, the poetries and prayers that rose from the rocky, dusty, sometimes fertile terrain of a land indeed holy.

it would be a couple years before i found out the reason the bespectacled fellow was heading out to synagogue early on those friday nights: that was the hour of the singles’ shabbat service. he was looking to meet a nice jewish girl, and theirs was the six o’clock service. oh, well. that didn’t quite work the way he’d intended.

nor did i ever expect to be so deeply entwined with the religion of ancient ancient times. though there were hints. way back in high school, i asked a jewish friend of mine if i could come to her family’s seder, the passover meal at which the story of the exodus is told and retold. she answered that her family didn’t really mark the occasion, but maybe that year they’d make an exception. so there i was at their table, turning the pages of the exodus story, searching for the hidden matzah at the end of the meal. i came back year after year.

and all these years later, i’m the one who opens the jewish cookbook as the holidays near. over the arc of time, we’ve inscribed customs into the trace of the year: rosh hashanah, the new year, is when lamb stew (a middle-eastern iteration with chickpeas, and raisins, and apples and rice) is on the stove, though this year, just the two of us, we opted for the modern-day jewish classic, chicken marbella from the silver palate cookbook.

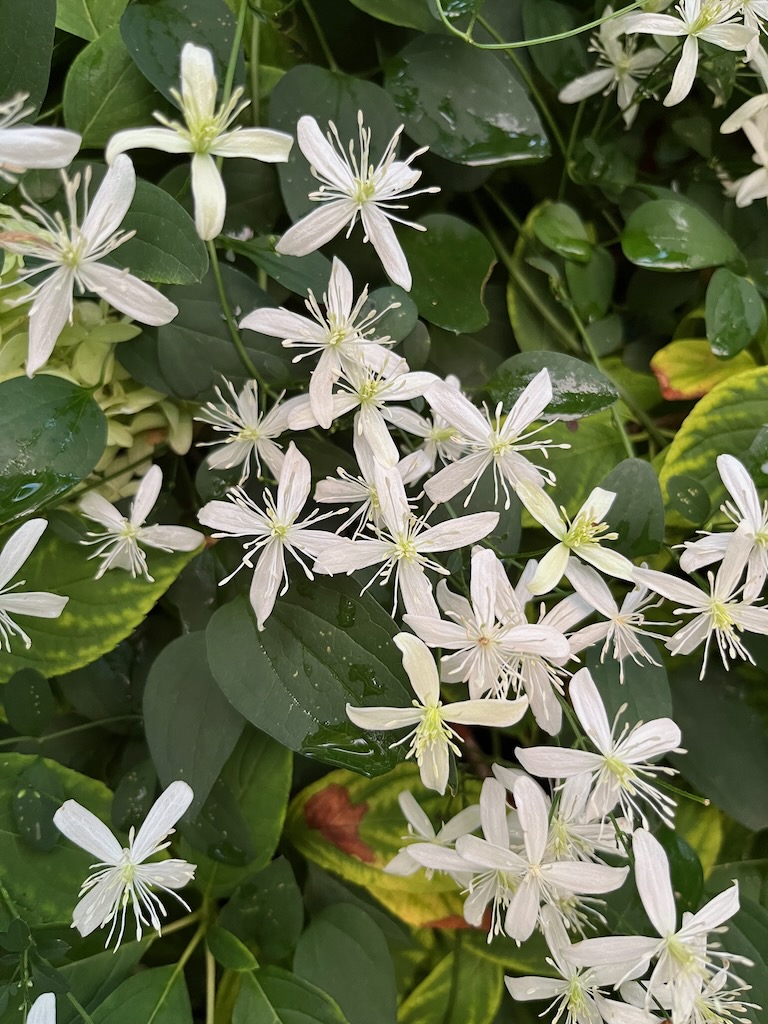

i crack open the prayer book too. crack it open weeks and weeks ahead of time, for the prayers are what draw me deep into the currents of the great river of judaism. awaken me to the mysteries and sumptuous beauties all around. remind me to see the miraculous in the most ordinary: the dust mote wafting by, the shadow of a tree, the call to pray “in the moments when light and darkness touch.” sometimes it’s the language, a simple line chiseled over time, that breaks me wide open, like this one: “prayer is our attachment to the utmost.”

let that one filter in…

sometimes i think my blessing is that i am still new to all this, so the way the words are unspooled is still fresh enough to catch my attention, my breath. i am often the one quietly gasping in the pews. or here at my kitchen table.

one last thing before i unfurl my prayer, my tefillah, for the new year: the other night at synagogue, just before the prayer for healing, the rabbi told of a midrash taught over time. she began by pointing to the eternal light that hangs above the arc where the Torah scrolls are kept. she noted that in the ancient temples the light that burned was from a wick floating in oil, specifically olive oil, the only oil allowed to burn in the eternal light. and then she went on to talk about the olive, the abundant small but ubiquitous fruit of the hillsides of the holy land. she noted that the oil from an olive is released only when it’s pressed, and crushed. and then, in that majestic humble way of hers, she taught us a lesson i’ll never forget: “when the olive is crushed it’s brightest light comes forth.”

ponder that the next time you feel the world pressing in from all sides, when you feel crushed. your brightest light might soon be burning.

here is my prayer for the new year. . .

tefillah for a sweet new year in the season of awe…

O One who robes this world in threads of crimson and bronze, who reaches in the paint pot for persimmon, goldenrod, and concord grape, the palette of autumn ablaze,

under newborn moon, under deep black dome of night, i bend my knees and pray…

i ask for blessing abundant. i ask stingily, you might think.

but then, you look around the world, see the tally from which i draw, and realize i’m barely beginning.

i pray first for forgiveness, for the sins of this selfish, self-obsessed culture of course, but more immediately and closer to the bone, for the sins of my own failings: my unwillingness to stray too far beyond the comfortable, to not muster the radical courage to cut a bold swath, to heal what’s deeply broken; for my inability to see my own blind spots; for the flippant dismissals i sometimes make too quickly; for being afraid, to the point that it occludes my seeing and breathing, my being.

i pray for peace, peace of nations and peace of each unsettled heart.

i pray for wisdom to discern that which lasts and that which crumbles over time.

i pray for grace which i define as radiance that will not fade in the face of shadow, will not step aside when life inflicts sharp elbow.

i pray for the hand that reaches out to dry the tears of the one whose cheeks are splotted, streaked, and sodden. even when, especially when, those cheeks belong to a someone we do not know. yet the simple presence of those tears signals how deep, how stinging, the hurt must be, the pain. i pray for the woman who sat beside me at synagogue and could not stanch her tears.

i pray for those who go through life fists clenched, driven by a fury that won’t allow unfurling. won’t release the tendons taut, won’t uncoil the hands God gave so we could do the work of loving, of reaching, and cradling in times of turbulence and tumult.

i pray for the echo of laughter’s peals rising from the kitchen tables, the diner counters, the park benches, those flat plains where good souls congregate to dig down deep and tell their stories.

i pray for morning light to rush in before eyelids flutter open so that when they do all is golden, nearly blinding, in its insistence to start the day awash in luminescence.

i pray for mothers who buried their children this week. i pray for the papas whose hearts were hollowed by deaths too soon, too impossibly inexplicable. i pray for memory to fill in the cracks, to begin to piece together the jagged edges of the shattered vessel that is the grieving heart.

i pray and i pray for the children––afraid, broken, scared out of their wits, looking into a night sky not for stars but for rockets’ red glare.

i pray for silence from the bombs and the hell screech of rockets.

i pray for those pummeled by rain — be it the rain of those rockets or the deluge of storm and hurricane winds.

i pray we see You in the sparks that animate the woods, the streams, the darkened skies. i pray that all the cosmos becomes as if a light-catching prism of holy wonder and wild astonishment that points to the One Creator God.

i pray we see You, too, in the gentle murmur of kindness, of tenderness, of heavenly mercy that is certain trace of Holy Presence.

i pray, dear holy, holy God, for these days of awe to fuel us for the long winter to come. let us stock the larder, fill the shelves that line the walls of heart and soul. let us go forth, each and every blessed day, fully awake to the miracle of those we love, and those we don’t yet know whose lives, like ours, contain untold tragedy as well as untrumpeted triumph, and whose wholeness any day just might depend on the goodness of those who do not pass them by unnoticed.

amen. and thank you.

what lines would you add to our prayer, communally or privately?

the gull above is diving into lake michigan to gather up a chunk of bread one of us has tossed into the water, a symbolic casting of our sins into the lake in an act of absolution.

the line, “prayer is our attachment to the utmost,” is from rabbi abraham joshua heschel, and the full line is: “unless we aspire to the utmost, we shrink to inferiority. prayer is our attachment to the utmost.”