ashes to ashes…

it is among the most profound teachings of any religion. and its point is found at the root of every sage, seer, and saint.

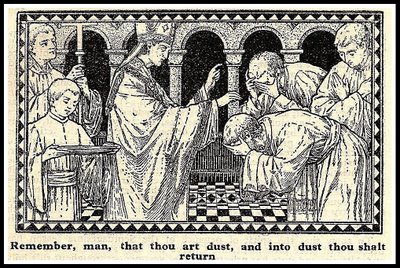

remember that you are dust, and unto dust you shall return.

some years, to be truthful, those words washed over me. not this year. no longer. it is the teaching at the core of my scan time epiphany, pressed onto my heart as i emerged from the months-long fog that followed the words from my surgeon, “it was cancer; i was surprised.”

we don’t have forever. our days are numbered. our time here is fleeting. we’re wise not to whittle away the hours. wiser still to work toward the nub, the holy nub, that i believe lies at the heart of why we’re among the blessed who got to draw a first breath in the first place.

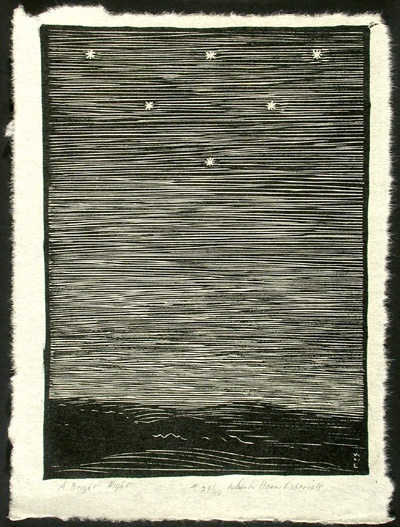

the odds of being born are stacked mightily against us; biology lays it all out at roughly 1 in 400 trillion (that’s 400 million million, or a 4 followed by 14 zeroes; i’m guessing that might be more than all the stars in the heavens. but what do i know?). we’re the ones who were allotted X number of days, who were given a holy task that’s ours and ours alone. and our slot to get it done, to reach toward holiness, to exude the light this world so desperately needs, is not without end.

so knew moses in the wilderness, imploring God: “teach us to number our days, so that we may gain a heart of wisdom.”

come the seventh century, a pope named gregory I pulled out the ashes to press against flesh, to remind the believers, to begin the 46 days then counted as Lent, a season of penitence before the coming of Easter. in judaism, the days of awe, from rosh hashanah, the new year, to yom kippur, the day of atonement, attention is turned to the mortal imperative: we will die. and we’d best make the most of our days. in islam, the inevitability of death is a core tenet, and muslims are taught to pray “as if this is your last ṣalāh (prayer).”

i live now with those teachings pressed hard against my flesh, whether you can see the smudge on my forehead or not. just so happens this week i walked around for a few hours looking as if i’d smudged a thumbful of dirt just above my eyebrows. and this week, a week in which i’ve spent so many hours trying to reach across to the other side, in search of a wink or a nod or a squeeze from two beloveds new to the other side, i found myself transfixed by the wisdom i wore for all the world to see.

i find it imperative. it’s the truth that fuels my every day, and all the hours within.

i live now with the palpable knowing that any minute the something stirring in my lungs (a something i likened to “a couch potato of a cancer” when my surgeon first described it as indolent, or lazy) could, in that surgeon’s inimitable words, “decide to leap off the couch and start running around the house smashing things.” the analogy here refers to the cancer detonating all throughout my lungs, a demonic pinball boinging wall to wall to any old air sac, the wee little bellows that allow you to draw in oxygen, blow out the junk that remains, the carbon dioxide we need to get rid of, lest we die of suffocation.

in my latest adventure in book writing, the book now awaiting yet another round of editing, a book whose working title is when evening comes: an urgent call to love (drawn from the great teaching of saint john of the cross who once wrote, “when the evening of this life comes, you will be judged on love,” and to which the mystic evelyn underhill then adds: “the only question asked of your soul: ‘have you loved well?'”), it’s the very point of the ashes—to dust you shall return—that animates every inkling, question, and meditation in the pages soon to be bound between covers.

in the year since i started writing that book, and in the almost three years since half my lung was snipped out of me, the choice to love well is one that rises over and over, a tide that won’t be quelled. it’s the most clarifying truth i’ve ever clung to. and it expands the walls of my heart, pushes me plenty beyond my comfort zone because i know my chances are dwindling. the next scan could come with the words that something is stirring. has made itself known. and i know those words will crumple me. knock the wind right out of me. at least for awhile. till i find my bearings again.

and so i live just ahead of those words, as if they’re always on the chase, running up from the rear.

the people i love who died last week, who crossed to the other side, were beautiful souls who loved so majestically, so magnificently, and both of whose lungs were filled with the damn cancer that would not relent. each loved till the very last breath. each didn’t want to die. each one was brave—mostly—till the end. and each one finally let go.

in so many ways, their holy nub did not die. their spirit, their joy, their infinite giving, it’s as alive as ever. maybe more so. i feel each of them. i hear their words, their laughter, the very lilt in the way they spoke every word. and their invisible presence stirs me robustly. maybe it’s that we were all in the cancer gulch together, shoulder to shoulder to shoulder. maybe it’s that we spoke a language so little known outside the republic of cancer; a language into which we’d been swept, a language where shadows are looming, a language propelled by unfiltered truth and urgency.

maybe i feel like it’s up to me to carry on their brilliant-beyond-description ways of being in the world. but that would be wrong. their work, their nub, lives on in the ways it will forever animate and rub up against ours. but my work is mine. and my days to do it are now. and your work is yours. and your days are now.

the God i believe in breathed into us a constellation of wonders, and set us on our way. as rilke once wrote in a poem i’ve long pressed to my heart, imagining God speaking to each of us as God makes us, before we are born, before we leave the womb of darkness, God “walks with us silently out of the night.” and as we near the precipice of the womb, the place where the daylight seeps in, God whispers: “Nearby is the country they call life. You will know it by its seriousness. Give me your hand.”

and so this work that is ours to do, in this time that will end, we are here for holy purpose. and our God is at hand.

ashes to ashes. dust to dust.

the time in between is our one holy chance.

how will we use it?

in the tiny chapel where i go to pray, and where this week the ashes were smudged on my head, i found these words from psalm 103 breathtakingly beautiful. . .

for [God] himself knows whereof we are made;

he remembers that we are but dust.

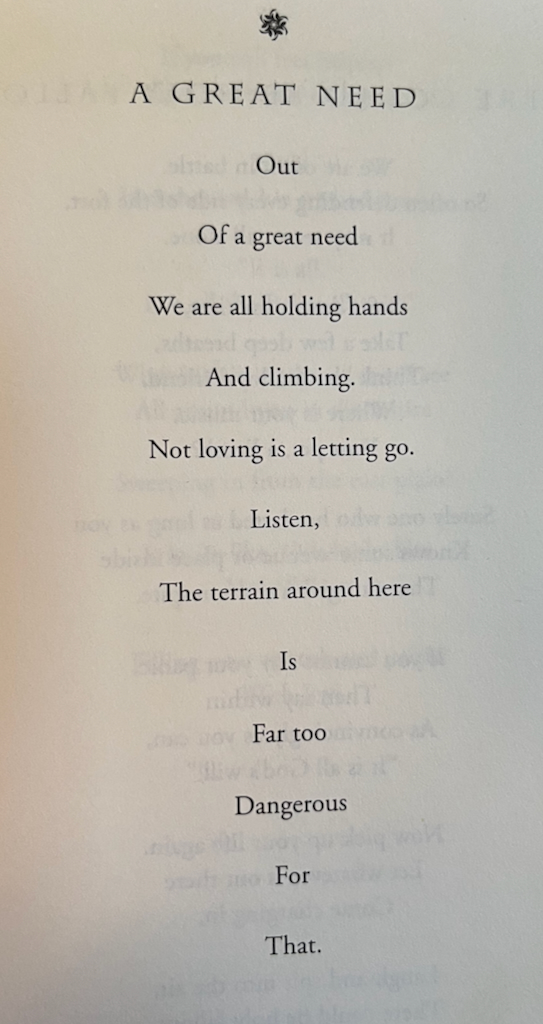

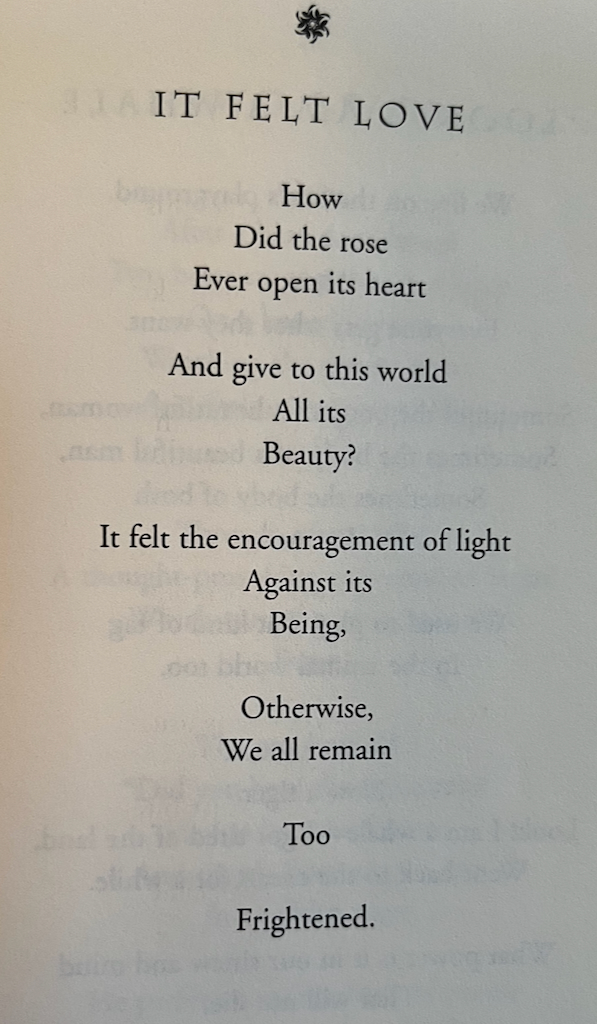

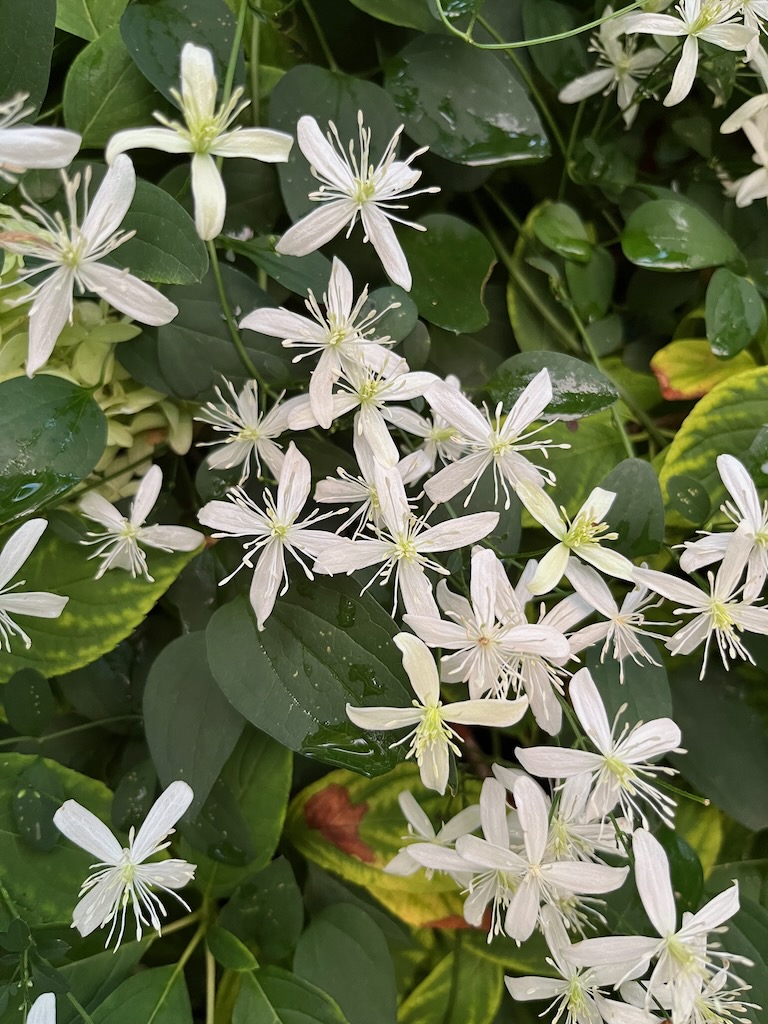

Our days are like the grass; we flourish like a flower of the field;

When the wind goes over it, it is gone, and its place shall know it no more.

may our time in the field be fruitful, may our petals unfurl fully as we drink in the sunlight. before the wind blows over us, and our time here is no more….

love, bam

sending special special love to the beautiful mama of one of the beauties who has crossed to the other side….i know that all of us here reach across the table in hopes of steadying your trembling hand, tissue at the ready to dry your flow of tears….