so close to the bone

uncharted is pretty much the most fitting descriptor for the cartography of cancer. undiscovered nooks hide in the shadows. though not all of it is somber. sometimes, with no warning, you find yourself among an unexplored parcel for the very first time.

i’m covered with goosebumps this week, not because my latest scan was ominous (it wasn’t) but because i am reminded again this week, viscerally so, how very damn thin this ice is—the ice that is any cancer, and mine in particular. i sat down with my oncologist the other day, and she spelled out so many truths about the merciless ways of cancer—how so many hit-or-miss variables make up each individual constellation, how some of mine fall in the you-don’t-wish-this column, and one or two don’t, how some cancers are “undruggable” (mine is) yet some of the drugs are so toxic you’re mostly relieved you don’t have to have them coursing through your veins—and it all becomes stunningly clear that there really is not much certainty or sense to the prognostication at play here. sometimes you make it through the labyrinth, sometimes you don’t. who’s to say what flicks the switch that plays out your story.

but that wasn’t the only reason for goosebumps.

a curious thing happens almost instantaneously and mysteriously when you find out you’ve been highjacked into cancer camp: you make fast friends. with the ones you find strolling around the campground, the ones who know the indignities of needle pokes and incision tattoos that now crosshatch your flesh; the ones who spout the most off-color jokes, and know all the words to the worries that keep you awake in the night; the ones who strip truth to the bone and don’t shy away from words that others dare not utter.

one of those friends died this week. bruce was his name, and not too many months ago, he was the one who all but talked me onto the airplane to new york to get a second opinion, when i—the one who never has had a taste for ruffling feathers, nor for appearing to second-guess authority—was so afraid to face the cold hard reality of a cancer center whose very name registers the seriousness with which cancer is to be taken. bruce told me all about his trek to mayo clinic, and insisted i get on that plane to sloan kettering. and when i got home, he checked in to make sure i’d stayed in one piece. his wife, eileen, also my close cancer buddy (and also with ratchety-vocal-cord voice), has been one of the ones who until now has made me laugh the hardest; lately, her texts have been tearing me apart, especially when she told me she’s mostly been crying herself to sleep these last couple months.

and just yesterday i was scrolling across the internet and bumped into the news that one of the fiercest patient advocates in the world of lung cancer, a woman whose cancer (diagnosed when she was 39, and recurred multiple times) has defied all odds for 16 years, has just started another round of radiation for two metastatic nodules on her chest wall.

when one of us goes down, the thud is felt by all.

and so, as if never before, i am looking out at the snow-caked garden, at the beefeater-sized snow caps atop all my birdhouses and feeders, and i am whispering, whispering, inaudible prayers of pure and profound thanks. for the miracle of another winter. for the quotidian phone call from one of my boys. for the chance to sit in a near-freezing kitchen to work side-by-side my second born. for the husband who leaves his car in the snow, so i can pull into the snowless garage. and who waits till i get home late one night to eat his bowl of cereal, while i slurp my soup.

and tough as it is to swallow, and bracing and sad as it all sometimes is, i am, in the end, more than a little grateful to be so fully awake to the whole of it: the friend whose courage i’ll carry; the blessing of a doctor who minces no words and delivers each one so bountifully, and with such tender, all-absorbing care; the miracle of any old friday or thursday or tuesday; the lungs that still work as mightily as they can; this place that lets me write it all down, because sometimes you just need a way to make sense of the blur, and this was one of those weeks.

not because i’m dying; because i’m alive.

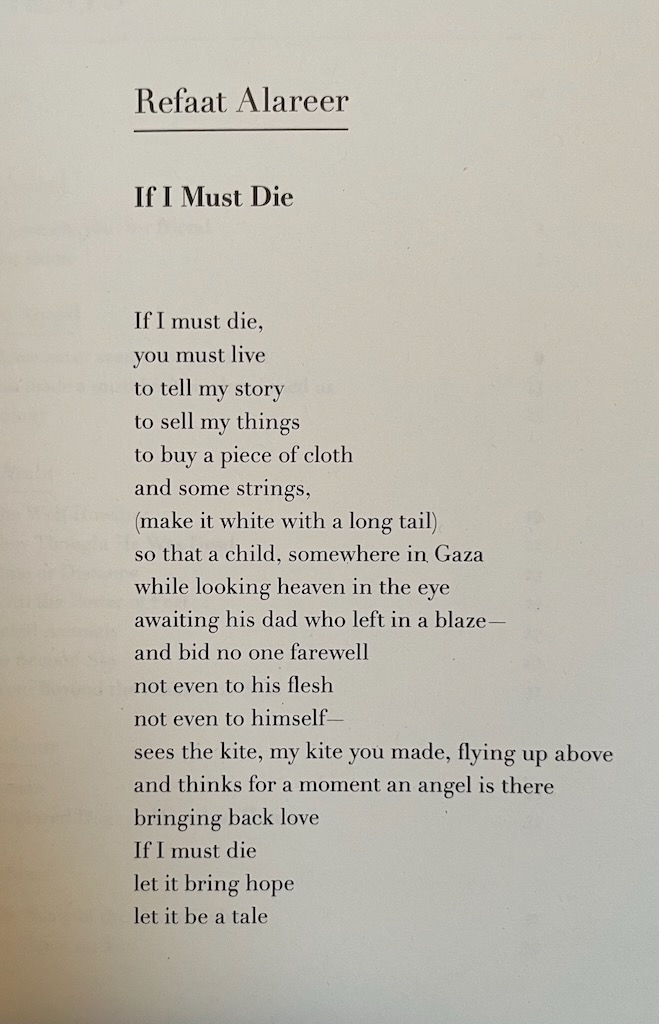

and with that, a poem that so deeply echoes the essence of all that pulses through me these days, and is, in many ways, the core message of book No. 6 now in the pipeline….

Praise What Comes

surprising as unplanned kisses, all you haven’t deserved

of days and solitude, your body’s immoderate good health

that lets you work in many kinds of weather. Praise

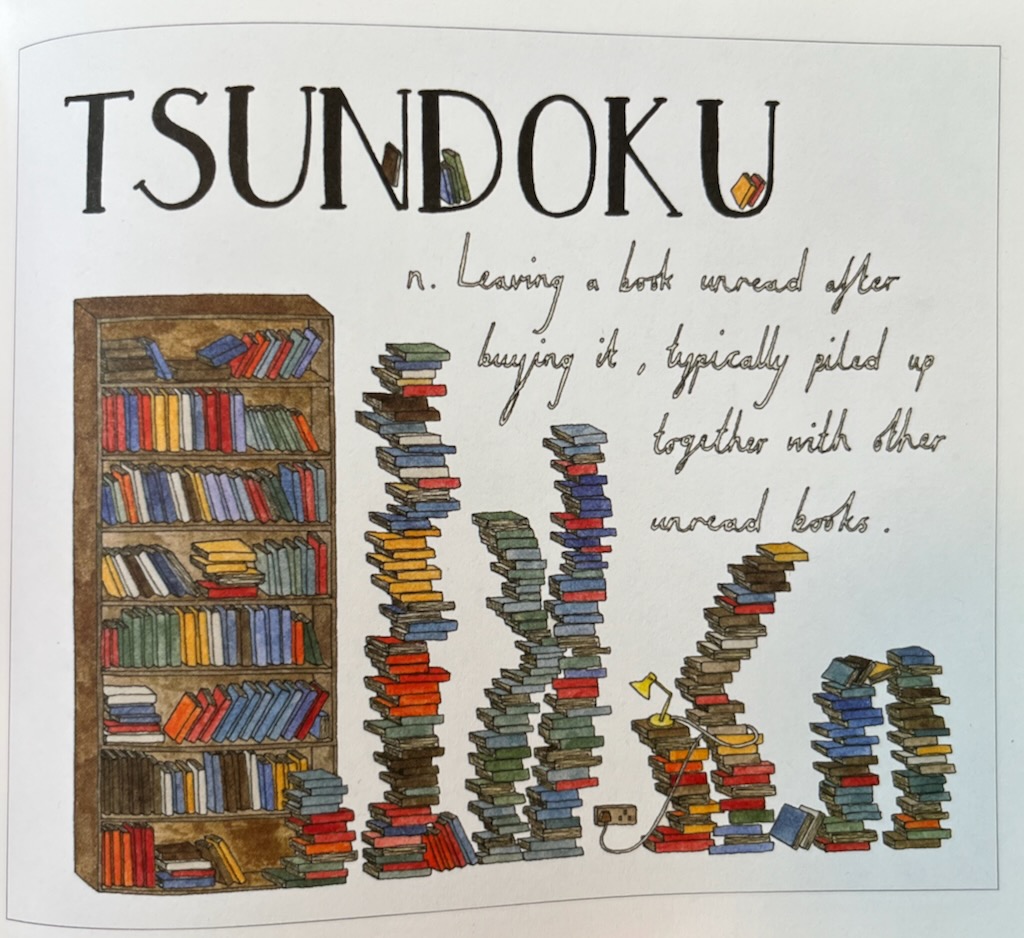

talk with just about anyone. And quiet intervals, books

that are your food and your hunger; nightfall and walks

before sleep. Praising these for practice, perhaps

you will come at last to praise grief and the wrongs

you never intended. At the end there may be no answers

and only a few very simple questions: did I love,

finish my task in the world? Learn at least one

of the many names of God? At the intersections,

the boundaries where one life began and another

ended, the jumping-off places between fear and

possibility, at the ragged edges of pain,

did I catch the smallest glimpse of the holy?

~ Jeanne Lohmann ~

(The Light of Invisible Bodies)

Jeanne Lohmann was a Quaker poet, and one of the very favorites of the great Parker Palmer. as a wee bonus i am adding here the last stanza of another one of her beauties, “what the day gives.” she is a poet in whose work i shall be poking around. here’s the stanza:

Stunned by the astonishing mix in this uneasy world

that plunges in a single day from despair

to hope and back again, I commend my life

to Ruskin’s difficult duty of delight,

and to that most beautiful form of courage,

to be happy.

and finally a poem from one of my favorite irish poets, eavan boland, passed along to me by one of my favorite humans. simply because it’s so perfectly, perfectly glorious…..and the very definition of love in its highest order….

Quarantine

by Eavan Boland

In the worst hour of the worst season

of the worst year of a whole people

a man set out from the workhouse with his wife.

He was walking—they were both walking—north.

She was sick with famine fever and could not keep up.

He lifted her and put her on his back.

He walked like that west and west and north.

Until at nightfall under freezing stars they arrived.

In the morning they were both found dead.

Of cold. Of hunger. Of the toxins of a whole history.

But her feet were held against his breastbone.

The last heat of his flesh was his last gift to her.

Let no love poem ever come to this threshold.

There is no place here for the inexact

praise of the easy graces and sensuality of the body.

There is only time for this merciless inventory:

Their death together in the winter of 1847.

Also what they suffered. How they lived.

And what there is between a man and woman.

And in which darkness it can best be proved.

From New Collected Poems by Eavan Boland. Copyright © 2008 by Eavan Boland.

what brought you this week the deepest sense of how very blessed you are, to be alive and able to exercise love in whatever form fills you the most?

p.s. i hope all of you who still find a seat here (after all these years; 19 next week!), or who are here perhaps for the very first time, know how very very deeply this space, and your presence here, has become one of the polestars of my life. my calendar is set by writing the chairs (every friday morning without fail); six books now have first been seeded here; and the kindness circle we’ve all built together is rare and precious in the fullest sense of that word. as the world around us has grown harsher, and the rules of engagement seem to be shifting at rapid and dizzying pace, we have rooted ourselves more and more deeply in the gentle art of caring gently for each other, offering up wisdom by the ladleful (and i mean the wisdom you offer me, offer all of us), and lifting our kindness off the page (aka screen) and into the real living, breathing world. among the things for which i am so deeply grateful, all of you dwell at the core of my heart. bless you.