ode to my fairy gardenmother: one last love note. . .

Mostly, this is a love letter. One I might have tucked in the pine coffin now buried beneath a foot-and-a-half of Chicago’s clumpiest earth, earth we shoveled onto it, one full spade at a time. The one to whom I write this, though, my fairy gardenmother, is not one ever confined by boxes or borders or hard lines scrawled in the dirt. She, my Marguerite, was as free a spirit as they come. So I cast this to the wind, and know she will catch it.

Marguerite made beauty for a living. She sowed joy in abundance. Not a single root or shoot was tucked in the earth or tied to a trellis without the ringing sound of her laughter.

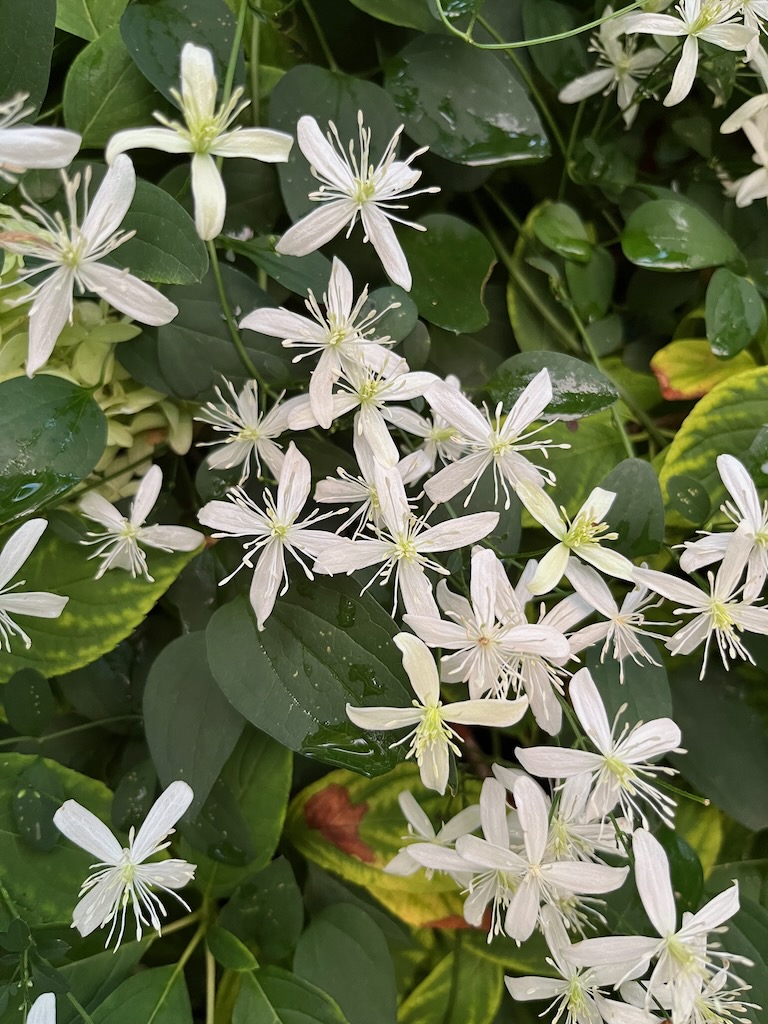

She bequeathed me beauty, her beauty and that of this holy earth. And grace, and a tidepool of peace, the sort that settles deep within, calming what had long been a turbulence. It all came in a litany of botanic derivative, a litany I water and witness: tree peonies, fuchsia and ruffled and broad as a dinner plate; oakleaf hydrangea, its bottle-brush blooms now bursting in time for the Fourth of July. Pieris japonica (sometimes known as lily-of-the-valley shrub, or flame of the forest) whose delicate white star-blooms are the petit point of late springtime, stitched along the bluestone path that bends toward my front door. A dwarf lilac that defies its definition and perfumes profusely my brick walk out back. My garden blooms with acanthus, the ancient Greek thistle of endurance and immortality, and white bleeding hearts that, as instructed, seem to be on the verge of spilling succulence drop by drop by drop. Everywhere, the vanilla scent of Jack-in-the-pulpit rises. There are ferns in abundance, and climbing hydrangea who wouldn’t be daunted by Everest. And about a dozen other beauties whose names I often forget, and when I do I’d text her, and she’d remind me, always with annotation of what she loved most about it. And another something I might want to try.

If I tried to describe her, I’d begin with her face. Her face was alive, was radiant, was always revved up in joy. Or deep concentration. Her laugh came easy, so easy. Her limbs flowed. She was a ballerina in the everyday. Clogs buried in garden, wielding a shovel or pruners, she swayed with the wind, with the whims, with purpose.

She planted my secret garden, the one that meanders along the side of my house, from my writing room window, past the kitchen door, and into the garden out back. It’s the place I’d point to if pressed to answer the question: Where did you finally find your long-sought peace? It was there in the garden that Marguerite grew.

I first met Marguerite a garden ago, back in 1991, months after we married, my beloved and I. The very day we wandered into the old Victorian that became our house for a decade, the house to which both our boys first came home, the house that held so many joys and so many sorrows, Marguerite was there. She was packing up boxes with Jim the sculptor who was dying of AIDS, and who would soon leave us his beautifully sculpted three-story house (and a set of Old Willow dishes besides). They wept and wailed and laughed together. We heard the echo of their affections before we saw them, and when we climbed the stairs there she was: radiant, a mop of blond curls, eyes hazel and sparkling.

She knelt beside me summer after summer, teaching me much of what I know about what grows in a garden. We wandered nurseries and tree lots. We planted according to her unorthodox teachings. When anything ailed, she knew the fix. Or we yanked it and started again.

My jewel box of a tiny urban garden, one where the alley rats dared not roam for the fierce farm cat who patrolled it, grew to be a wonder. One whose measure in my mind far exceeded a yardstick.

When at last we decided we’d finished our work, at least for the time being, Marguerite and Ted, her rabbi of a husband who presided over a congregation of his psychotherapy clients, came by one late summer’s evening to bless the little plot. In a story I love so much I included it on pages 37 and 38 of The Book of Nature**, Ted offered up fertility prayers for my garden, that it would blossom and bloom, and multiply. Four months later, on the brink of my 44th birthday, after eight years of broken hearts and infertility, I discovered that I was the one blossoming and multiplying. I was “with child,” as the Bible would put it. I always giggled that Ted had mixed up his fertility prayers, and pulled out the ones for the barren woman instead of the ones for the garden.

And so, of course, and ever since, Marguerite is the one to whom I turned with every garden question, and every delight as it bloomed. When Ted died not quite two years ago, I knew Marguerite’s heart was shattered. And there was no glue in the world to put it back together. But I didn’t know it would kill her.

I now know that it did. For she died on Monday, and was buried on Tuesday. And ever since I’ve been strolling through my garden, stopping to marvel here, stooping to deadhead there. I’ve been shlepping my hose, and giving big drinks to each and every bloom bequeathed to me by my Marguerite.

Marguerite will always bloom in my garden. Her longtime sidekick, David the cop, is coming soon to help me dream once again. There is a plot under the ornamental lilac and the row of burning bush, and I have named it Marguerite’s Garden, and I will be planting it before the month of her death turns to August.

And it will be abundant in beauty. Because that’s what Marguerite taught me to grow. And that will never die.

Marguerite’s genius in the garden spread far beyond our little block of Wellington Avenue, 60657. When she couldn’t be contained, she launched a for-hire garden crew (a motley crew counting two cops, a U of C theology grad fluent in Mandarin Chinese, a commodities trader, a banker, and a pet photographer) with a seasons-long waiting list. She planted tulips by the thousands up and down Boul Mich, Chicago’s grand Magnificent Mile. She planted the city’s lushest rooftops and balcony gardens. She was a connoisseur of miniatures, and knew how to cram the most in the least. She opened a dream of a flower shop in Andersonville, aptly named Marguerite Gardens, and twice daily received imports from her beloved Netherlands. The shop, with the bell that tinkled as you walked in, held a European-style flower market, and was stuffed to the rafters with eighteenth-century antiques, from bird cages to terraria. Aptly, she was named for the daisy whose name means “pearl” in French, and is the bloom from which petals are plucked in the prognostication game, “he loves me, he loves me not.” Married for 43 years to the inimitable, unorthodox, Yale-educated rabbi and psychotherapist, Theodore Gluck, Marguerite died 656 days after Ted, three days short of what would have been his 95th birthday. Marguerite was 75.

**excerpt from pages 37 and 38, Marguerite’s star turn in The Book of Nature, in which i describe that first garden we planted and blessed together…

. . .That garden—where a priest, a rabbi, and a tight circle of people we love gathered for blessings shortly after the births of each of our boys; where baby bunnies and nestlings and goldfish were buried after premature deaths; where our stubbornly resistant house cat mastered the art of escape—that plat of earth became as sacred to me as any cloister garth.

Not only was it where I knelt to teach my firstborn the magic of tucking a spit-out watermelon seed into the loam and, each morning after, tracking its implausible surge. During seven long years of miscarriage after miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy and emergency surgery, and doctors finally telling us to give up hope, I dug and I dug in that garden, all but willing the tiniest bulbs and tenderest sprouts to beat impossible odds, refusing to let anything else die on my watch. And then, at the end of one summer, as the crab apples were starting to turn, a rabbi who lived down the block came by with his wife, whom I’d long called my fairy gardenmother for her magical ways and her unbroken guidance. Standing under the stars, the rabbi, his wife, and I, we blessed the garden itself, casting prayers and sprinklings of water. By that Christmas, I was pregnant, with nary a drop of medical intervention. Just shy of forty-five when that blessing of a baby arrived the next August, I’ve always wondered if maybe the rabbi mixed up the garden fertility prayers.

It’s all a holy whirl—that intricate and inseparable interweaving that is the cosmos.

one poem this week, from a bouquet of many i plucked:

Desiderata

Go placidly amid the noise and the haste, and remember what peace there may be in silence. As far as possible, without surrender, be on good terms with all persons.

Speak your truth quietly and clearly; and listen to others, even to the dull and the ignorant; they too have their story.

Avoid loud and aggressive persons; they are vexatious to the spirit. If you compare yourself with others, you may become vain or bitter, for always there will be greater and lesser persons than yourself…

Exercise caution in your business affairs, for the world is full of trickery. But let this not blind you to what virtue there is; many persons strive for high ideals, and everywhere life is full of heroism…

Take kindly the counsel of the years, gracefully surrendering the things of youth…

Beyond a wholesome discipline, be gentle with yourself. You are a child of the universe no less than the trees and the stars; you have a right to be here.

And whether or not it is clear to you, no doubt the universe is unfolding as it should. Therefore be at peace with God, whatever you conceive Him to be. And whatever your labors and aspirations, in the noisy confusion of life, keep peace in your soul. With all its sham, drudgery and broken dreams, it is still a beautiful world. Be cheerful. Strive to be happy.

by Max Ehrmann

and in extra case you’re extra curious, here’s a story i wrote for the chicago tribune back in may of 2000 about my friend marguerite and her garden crew: https://www.chicagotribune.com/2000/05/07/planting-away-again-in-marguerite-aville/

who taught you much of what you know about beauty and joy and free-flowing grace? might you tell us a bit of that story….

one last time: love story of a lifetime. ted + marguerite = forever and ever. amen.