turn to sweetness

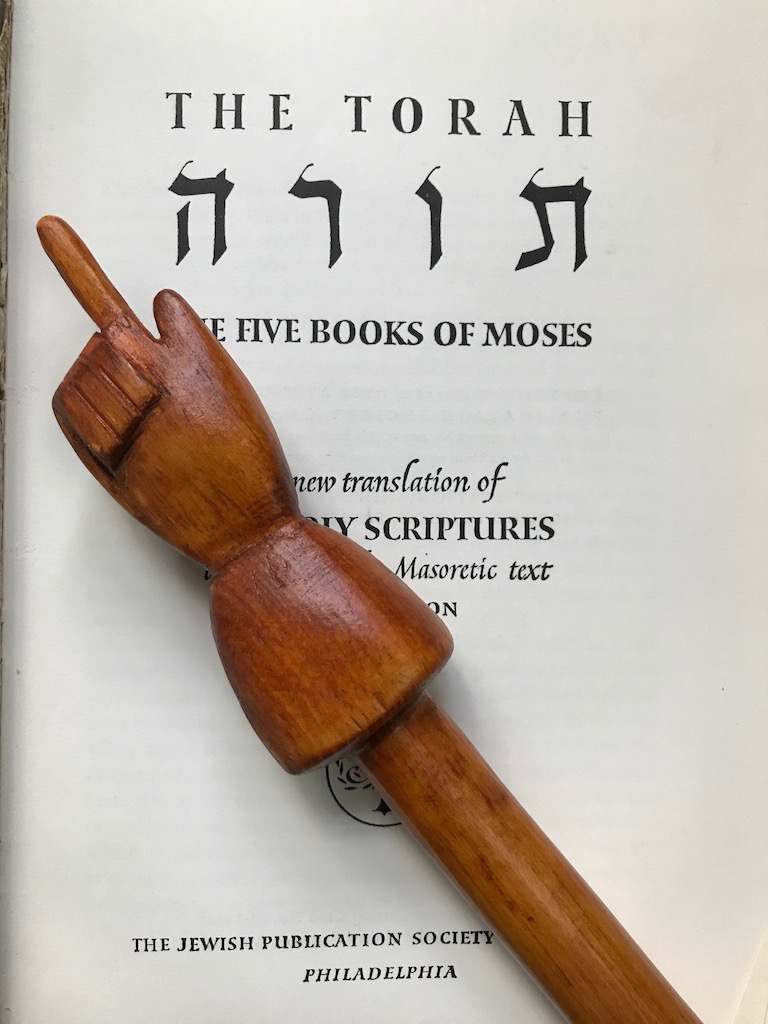

the new year calls for sweetness. the Jewish new year, i mean. it’s encoded, in fact, in the Talmud, the nearly-as-old-as-time, all-you-need-to-know guide to living Jewishly, a sacred compendia of rabbinic discourse, debate, and back-and-forth covering ancient teachings, law, and theology, and it gets down to the nitty gritty of what to eat when, and certainly on Rosh Hashanah, one of the highest of the high holy days. it’s spelled out, right there in tractate Keritot 6a (truth be told, i am not quite sure what a tractate is, but i’m surmising it’s something like a bullet point), where a certain sage named Abaye in the second century suggests that eating certain foods might bring on good things in the new year (this might explain the thinking behind the famous sheet cake scene with tina fey from saturday night live*). these sacred foods for the new year are called simanim, and while the Talmud explicitly names fenugreek, dates, leeks, and beets, it merely points broadly to sweetness. honey wended its way into the Rosh Hashanah traditions way back in the seventh century. which means the jews have kept the bees in business for a long, long time. and the dipping of apples in honey is a tradition that waited till the 16th century, which means we’ve been dipping now for 500 years.

and i realize i am steering well off course here, but i find myself in a rabbinic hole of infinite delight and must let you know that jews, known as lovers of wordplay, have prayers to accompany each of those prescribed foods (derived from the shared linguistics in the hebrew root), and the way it worked was that the particular prayer was prayed, followed by the eating of said foods, and this whole shebang was known as the simanim seder. here are a few of the foods and the prayers they inspired:

personally, i think we should all be loading up on dates and beets. but now i am really off in the ditch, and shall return myself to more linear thinking. . .

we were musing about honey, or at least i was. and since this is ultimately going to be a story about honey cake, i’m in the midst of explaining how we got there. how i wound up shoving a bundt pan of sumptuous honey-doused batter into my unreliable but deeply lovable ancient commercial-grade oven.

i tend to be someone who gloms onto traditions. and, given that these days, i spend a lot of time musing about time and the passing of years, i was suddenly struck—even though i am the farthest thing from a baker—with the question of whether there was some heirloom recipe for the holiday that i might have been missing. so i struck out to the best family baker, my brilliant and beloved sister-in-law brooke of the upper east side, and before the text with the query could possibly have registered in her wee little phone, she shot back the recipe she’s been baking for years. she noted that it was a super hit, and she noted that it was a family heirloom not in the traditional since, as her mother/my mother-in-law staked her claim to feminism by not knowing her way about the kitchen, and thus might not have baked in her life, dear brooke had made it a family tradition, one that secured its position the very first year she baked it when all that was left was a plate full of crumbs.

that’s all the convincing i needed, so i (practically as inept a baker as my late, great, mother-in-law) leapt aboard. i wheeled my grocery cart wildly through the store, plucking spices off shelves, fresh-squeezed OJ from the cooler, stocking up on fresh bags of flour, baking soda, baking powder (for the ones currently on my shelves had likely turned to clay, the subjects of years of idle waiting), and i set myself to baking. words being more my thing, i immediately gave it a name, this honey cake of famed repute. since dear brooke had clued me in its familial origins with this trademark hilarious note —”Considering that Mom’s recipe for the New Year was attending someone else’s party, this is our (1 generation = me) tradition.”—i immediately dubbed it Gen One Honeycake, and so it’ll stick. i also informed my boys they’d best follow along, for it was now incumbent upon them and their children’s children to crank the ovens every Rosh Hashanah, and pull out the whiskey and OJ.

excuse me, you say? where does the whiskey come in, and why are we talking cocktails so early in the morning? well, this famed honey cake, so dense it shall bulk your biceps as you ferry it to the table, is loaded: whiskey (or rye), OJ, a cup of coffee, a cup of honey, and a shuk‘s worth of spices. (a shuk is the israeli name for an open-air spice market)

aunt brooke continued, holding my hand (long-distance) the very whole way:

“It’s Marcy Goodman’s honey cake and it’s a fan favorite. Use the whiskey and use the sliced almonds in the recipe. And if you have whole wheat flour, sub in 1/2 c wheat flour for 1/2 c white flour. Make it in a tube pan. It’s a big dense cake.”

much to my amazement i found it pure delight to stand at the counter dumping in this and that, and stirring as directed. as the smell rose from the bowl, i began to understand the soothing powers of baking. and now wonder if it’s seductive enough—and sufficiently sedative—to carry me through the next 1212 days (inauguration 2029).

because my oven is, as i’ve mentioned, a recalcitrant behemoth, i’ve no idea whether it rose to the necessary 350-degrees Fahrenheit, and suspect it was probably my fault that the cake, despite its extra five minutes in the oven, decided to collapse round the middle (a flub fixed first by dumping extra almond slivers into the hole, and then duly disguised by brooke’s suggestion of stuffing the hole with rosemary sprigs, which i happened to have growing out back).

by the time i carried it to the table, where eager forks awaited, i felt my chest puffing out just a bit, swelled with pride at picking up the family slack. we now have ourselves a tradition. and my boys, by edict of their mother, shall carry it on, far into the next and the next and the next generation. may it always be so.

with no further ado, for i’ve tarried long enough here, i offer you the famed aunt brooke gen one honey cake, courtesy of one marcy goldman, reigning queen of the honey cake whoever she is. the version here was posted on deb perelman’s smitten kitchen site, and comes along with notes at the end, worth reading for their spicy humor.

Gen One Honeycake, from famed family baker BJKR, courtesy deb perelman’s Smitten Kitchen, courtesy marcy goldman (a cake with lineage!)

SERVINGS: 16

TIME: 20 MINUTES TO ASSEMBLE; 1 HOUR TO BAKE

SOURCE: MARCY GOLDMAN’S TREASURE OF JEWISH HOLIDAY BAKING

See Notes about recipe changes at the end of the recipe.

3 1/4 cups plus 2 tablespoons (445 grams) all-purpose flour (see Note)

1 3/4 teaspoons baking powder (see Note)

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon kosher salt (see Note)

4 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1/2 teaspoon ground cloves

1/2 teaspoon ground allspice

1 cup (200 grams) vegetable or another neutral oil

1 cup (320 grams) honey

1 1/2 cups (300 grams) granulated sugar

1/2 cup (110 grams) light or dark brown sugar

3 large eggs

teaspoon vanilla extract

1 cup (235 grams) warm coffee or strong tea (I use decaf)

1/2 cup (120 grams) fresh orange juice, apple cider, or apple juice

1/4 cup (60 grams) rye or whiskey, or additional juice

1/2 cup (50 grams) slivered or sliced almonds (optional)

Pan size options: This cake fits in two (shown here) or three loaf pans; two 8-inch square or two 9-inch round cake pans; one 9- or10-inch tube or bundt cake pan; or one 9 by 13 inch sheet cake.

Prepare pans: Generously grease pan(s) with non-stick cooking spray. Additionally, I like to line the bottom and sides of loaf pans with parchment paper for easier removal. For tube or angel food pans, line the bottom with parchment paper, cut to fit.

Heat oven: To 350°F.

Make the batter: In a large bowl, whisk together the flour, baking powder, baking soda, salt, cinnamon, cloves and allspice. Make a well in the center, and add oil, honey, granulated sugar, brown sugars, eggs, vanilla, coffee, juice, and rye. [If you measure your oil before the honey, it will be easier to get all of the honey out.]

Using a strong wire whisk or in an electric mixer on slow speed, stir together well to make a well-blended batter, making sure that no pockets of ingredients are stuck to the bottom.

Spoon batter into prepared pan(s). Sprinkle top of cake(s) evenly with almonds, if using. Place cake pan(s) on two baking sheets, stacked together (which helps the cakes bake evenly and makes it easier to rotate them on the oven rack).

Bake the cake(s): Until a tester inserted into a few parts of the cake comes out batter-free, about 40 to 45 minutes for a round, square, or rectangle cake pan; about 45 to 55 minutes for 3 loaf pans; 55 to 65 minutes for 2 loaf pans (as shown), and 60 to 75 minutes for tube pans.

Cool cake: On a rack for 15 minutes before removing it from the pan. However, I usually leave the loaves in the pan until needed, as they’re unlikely to get stuck.

Do ahead: This cake is fantastic on day one but phenomenal on days two through four. I keep the cake at room temperature covered tightly with foil or plastic wrap. If I want to bake the cakes more than 4 days out, I’ll keep them in the fridge after the first 2 days. If you’d like to bake them more than a week in advance, I recommend that you freeze them, tightly wrapped, until needed. Defrost at room temperature for a few hours before serving.

Notes:

Size: These days, I bake this cake in two filled-out loaves, as shown, instead of 3 more squat ones. My loaf pans hold 6 liquid cups; they’re 8×4 inches on the bottom and 9×5 inches on the top; if yours are smaller, it might be best to bake some batter off as muffins, or simply use the 3-loaf option.

Flour: After mis-measuring the flour many years ago and baking the cake with 2 tablespoons less flour and finding it even more plush and moist, I’ve never gone back. The recipe now reflects the lower amount.

Baking powder: The original recipe calls for 1 tablespoon of baking powder, but I found that this large amount caused the cake to sink. From 2011 through 2023, I recommended using 1 teaspoon instead. But, after extensive testing this year, I’ve found that a higher amount — 1 3/4 teaspoons — keeps this cake perfectly domed every time, and even more reliably than the 1-teaspoon level.

Salt: The original recipe calls for 1/2 teaspoon but I prefer 1 teaspoon.

Liquids: This is address the question that comes up in at least 30% of the 1115 comments to date: “What can I use instead of whiskey?” and/or “What can I use instead of coffee?” The original trifecta of liquids in this cake [coffee, orange juice, and whiskey] is unusual and wonderful together, and I still think the perfect flavor for this cake. But if you want to omit the whiskey, simply use more orange juice or coffee. If you want to omit the coffee, simply use tea. If you don’t want to use tea, use more juice. If you don’t want to use orange juice, my second choice liquid here would be apple cider (the fresh, not the fermented, kind), followed by apple juice.

Apples and honey: It’s a whole thing!

Sweetness: The recipe looks like it would taste assaulting sweet but you must trust me when I say it doesn’t. But, if you reduce the sugar, any one of them, you will have a cake that’s more dry. You can still dial it back, but do understand what the adjustment can do to the recipe.

Flavor: Finally, this is every bit as much of a spice cake as it is a honey cake. Honey isn’t the most dominant flavor, but it’s one of many here that are harmonious and wonderful together. It smells of fall in a way that a simmer pot of $60 candle could never. I hope you get obsessed with it too.

that’s it, sweet friends. certain we could all use a little sweetness at this turn in the year, where did you find sweetness this week?

*as promised, the tina fey sheet cake scene. (nod to faithful chair reader sharon of twin cities!)